Across the first four parts of this series, a pattern emerged:

Taken together, this points to a simple reality:

We’ve reached the end of the Blocklist Era.

For 30 years, email security has revolved around blocking “known bads”—malicious IPs, URLs, file hashes, and keyword patterns. But generative AI lets attackers generate effectively infinite variations of “bad.”

You can’t blocklist infinity.

If an attacker uses AI to generate the attack, defenders must use AI to understand and detect it. That’s the shift we call Semantic Defense.

Traditional Secure Email Gateways (SEGs) operate like a massive CTRL+F:

As we described in Part 2, AI breaks this model with Semantic Fuzzing :

To a keyword-based filter, these look nothing alike. To a human—or a system that understands intent—they’re the same request.

The intent is identical. The signature is different. Keyword scanners “see” a clean email. Semantic Defense sees a familiar playbook.

Semantic Defense moves beyond what the email literally says (syntax) to reason about how it was built and what it means.

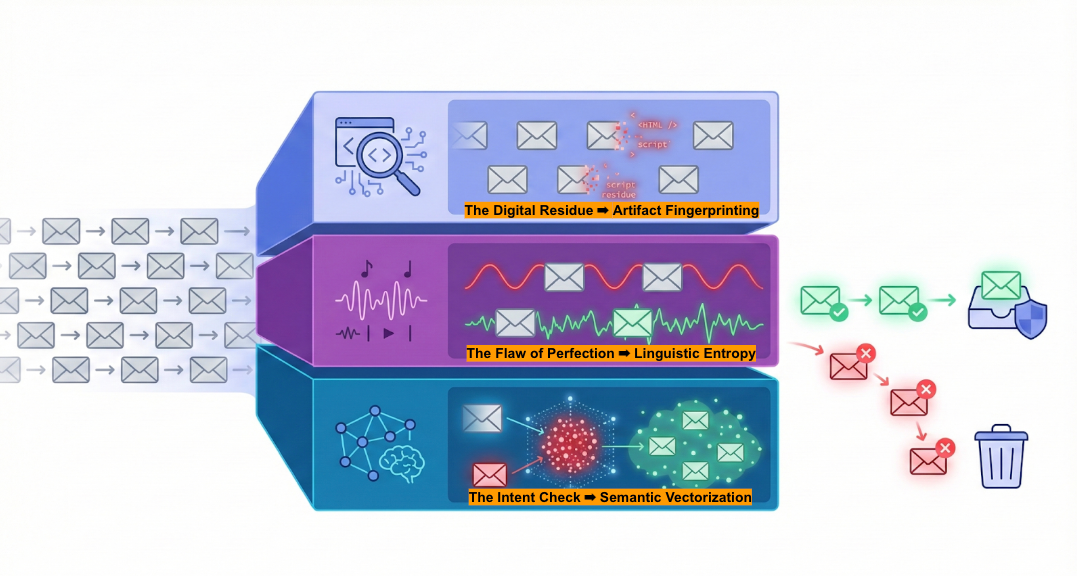

In our research, this takes the form of a three-layered approach designed to catch sophisticated AI attacks that slip past traditional gateways .

Even highly polished attacks leave machinery marks.

When AI agents or code assistants generate HTML templates and email scaffolding at scale, they often reuse invisible snippets of markup, leave behind tool-specific structures (like vo.dev or Copilot residue), or fail to fill in variables (e.g., {{NAME}}) .

These artifacts are not about the content of the email; they’re about the tooling that assembled it.

A Semantic Defense system acts as a fast filter here: it doesn’t “read” the email yet—it detects the factory that built it.

The next layer examines how the email is written.

Human writing is noisy. We mix short and long sentences, use odd turns of phrase, and vary our structure wildly. In data science terms, human language has High Entropy (high surprise) .

LLMs, by design, do the opposite. They optimize for the “most likely next word,” producing text that is statistically smooth and uniform .

That doesn’t mean you can eyeball a paragraph and instantly know it’s AI. But it does mean that, across enough samples, we can measure Linguistic Entropy. We are catching the attacker not despite the text being perfect—but because it is.

Finally, we ask the most important question: “What is this email actually trying to get someone to do?”

Here, Semantic Defense uses Vectorization—converting the email into a high-dimensional mathematical representation of its meaning (an embedding) .

This allows us to compare the email to clusters of known attack types. Even if the attacker changes every keyword or rewrites the text multiple times, the semantic distance between their lure and existing fraud patterns remains small .

This makes semantic fuzzing largely pointless. The surface changes. The underlying behavioral DNA of the request does not.

The landscape has shifted—for both attackers and defenders.

Attackers now treat cybercrime like a business, utilizing AI growth engines and exploits like the Context Gap. Defenders need to respond in kind:

That’s what Semantic Defense is about: understanding how a message was built, how it reads, and what it’s trying to make someone do—and using those signals to catch attacks that humans can’t safely shoulder on their own.

Where We Go From Here This series has traced the full arc: from the S-Curve of growth to the mechanics of the pipeline, the targeting of VIPs, and the failure of training.

If you’re ready to dig into the details, our full whitepaper walks through the statistical models, data sets, and real-world evasion patterns referenced in this series.

[Download the Full Report: AI-Powered Spearphishing at Scale]