“Do we send data to OpenAI?”

That is not the interesting question anymore.

The tougher version sounds more like this:

“Which of our vendors are sending our data to OpenAI, or to their own LLM stack, without ever showing up on our own architecture diagrams?”

The November 2025 Mixpanel–OpenAI incident is a warning shot on that second question. A targeted smishing campaign against Mixpanel did not leak prompts or keys. Instead, it exposed metadata about OpenAI API users and about CoinTracker customers: names, email addresses, organisation identifiers, device fingerprints, rough location, and usage context. On paper, that is “just analytics.”

In practice, it is a glimpse into how much of our operational reality flows through third parties that collect data, run it through someone else’s model, and retain detailed telemetry around it.

This post uses Mixpanel as the case study, but the point is broader: your AI attack surface is no longer just your own chatbot or in-house models. It is every SaaS tool with an SDK and a hidden dependency on OpenAI, Anthropic, or a home-grown model trained on your data.

Here is the short version of the story.

In early November 2025, Mixpanel employees began receiving SMS messages that looked like urgent notices from internal IT or an identity provider. One of those messages led to a fake login page that mirrored the real one. An employee entered their credentials and completed multi-factor authentication. The attacker, sitting in the middle, relayed those details to the real identity provider, captured the resulting session cookie, and gained access to Mixpanel’s internal support and engineering tools.

On November 9, that access was used to export datasets for a small set of high-value customers, including OpenAI and CoinTracker. The OpenAI-related export contained information about users of the platform.openai.com API interface: identities, organisation and user IDs, browser and operating system details, coarse location, and referrer data.

Mixpanel’s security team started incident response the same day. Accounts were locked down; forensics began. OpenAI did not receive the affected dataset and a full description of the blast radius until November 25. Public disclosures from Mixpanel, OpenAI, and CoinTracker went out on November 27.

OpenAI’s own infrastructure was not compromised. CoinTracker’s core systems were not compromised. The breach lived entirely inside Mixpanel’s environment, yet it still produced a detailed map of who uses OpenAI’s APIs and how, and a sensitive slice of CoinTracker’s user base.

On a classification sheet those fields often get labelled as low sensitivity. To an attacker, they are rich targeting data.

You can file this under “third-party breach” and move on, but that misses the bigger change.

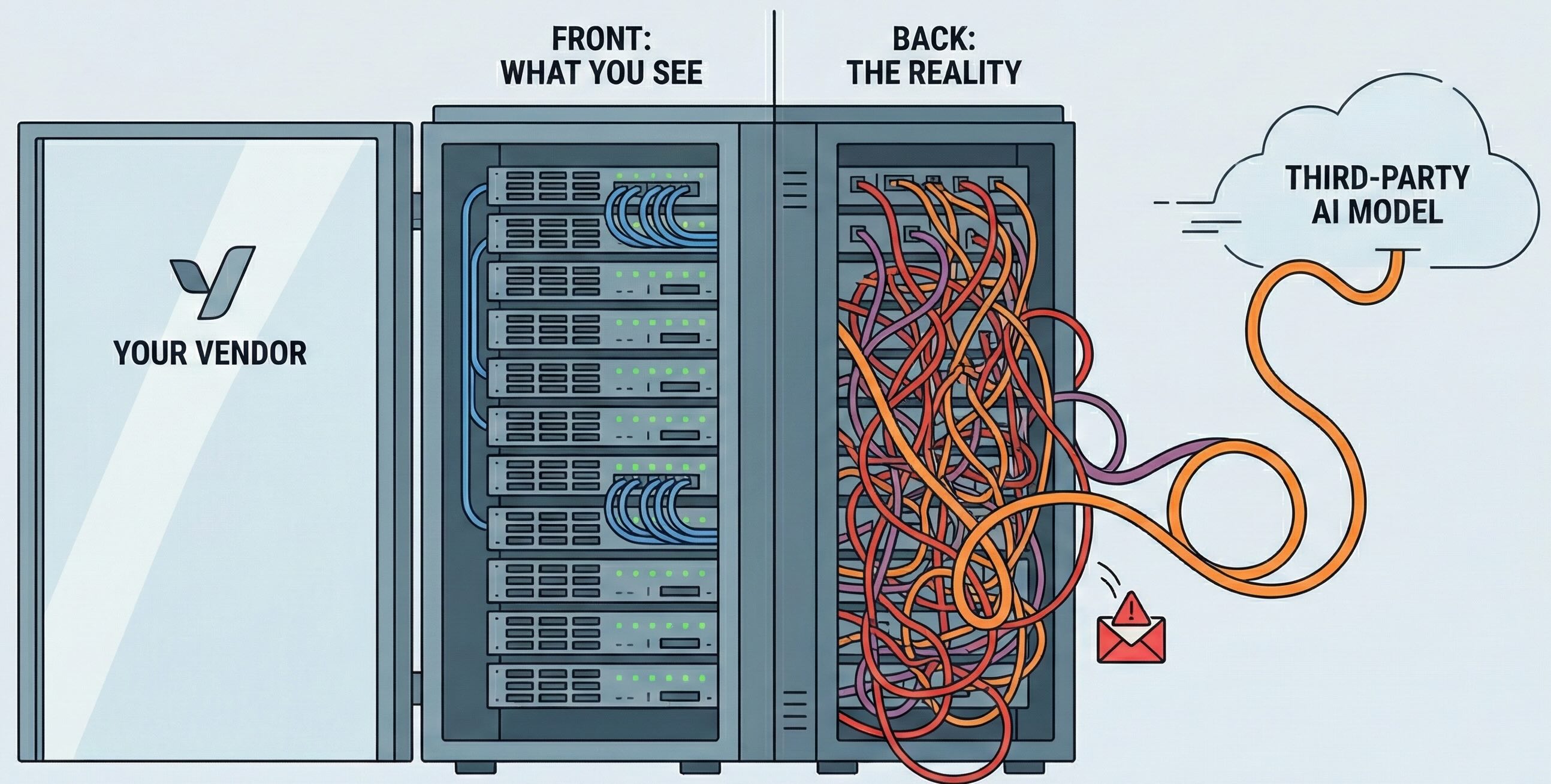

Vendor access patterns have shifted. Analytics tools, CRMs, ticketing systems and “copilot” products no longer just store logs. Many of them now send data to OpenAI or Anthropic, or to custom models they have trained on pooled customer data. When they get compromised, the blast radius is no longer just rows in a database. It may include prompts, outputs, embeddings, and training sets, plus the kind of metadata Mixpanel just lost.

Mixpanel does not position itself as an AI company. It sells funnels and cohorts, not copilots. Even so, its incident shows how much power sits with any vendor that sits in the path between your product and the models you rely on.

If this is the impact when a non-AI vendor is breached, it is worth pausing to consider what it looks like when the breached vendor is an AI-first product whose entire value proposition is “we have a smarter model than you.”

Most organizations do not yet have a good answer.

The uncomfortable reality is that almost every meaningful stack now includes tools that quietly embed OpenAI or other LLMs, without anyone ever updating the risk register.

The pattern is familiar. A team adopts a SaaS product to solve a clear problem in analytics, CRM, support, code review, or security operations. A few months later, that product launches “AI features”: automatic summaries, suggested replies, auto-tagging, anomaly detection, or a “copilot” side panel. Under the hood, there is usually one of two things happening: direct calls to external LLM APIs, or a custom model trained on customer data.

Your data flows upstream into the vendor’s primary data store, into their retrieval indexes and embeddings, and sometimes straight into OpenAI or another provider using the vendor’s account. Logging is often extensive, “for quality.” Retention policies are not always clear.

On good days, this gives your team a smoother experience. On bad days, you end up fielding questions from a regulator, a board member, or a key customer, trying to explain which models saw which data and whether you have any control over that.

The Mixpanel incident did not involve model training data, but it did expose the amount of leverage that sits with a vendor who tracks how you use someone else’s AI platform. It is not a stretch to imagine similar incidents where the breach hits a vendor whose product is itself a model trained on your tickets, mailboxes, or contracts.

There is a separate class of vendors whose product is inseparable from their model. Think of support copilots that read every ticket, AI SOC assistants that ingest alerts and email, sales tools that listen to calls and read proposals.

From the user’s perspective, this is great. Search in natural language, ask follow-up questions, click once to perform a task. From the security and privacy side, you need sharper questions:

The more your teams lean on a vendor’s model instead of your own, the more you should assume that a breach at that vendor is an AI exposure problem, not just a database incident.

All of this still sounds abstract until you look at what an attacker can do with it.

Go back to the Mixpanel–OpenAI dataset. The attacker now knows who many of the API users and organisation admins are, has their email addresses, has organisation and user IDs tied to OpenAI, and has device, browser, and location fingerprints plus referrer context.

It does not take much creativity to write the next campaign.

Imagine an email to an API admin that references their city, their role, and the Mixpanel incident, and points them to a convincing but fake OpenAI login page in the name of “key rotation” or “incident review.” The same story can be replayed in Slack or Teams messages that appear to come from internal security, in SMS that reference the vendor breach, or in LinkedIn messages from a fake trust and safety profile.

The breach is rooted in Mixpanel’s infrastructure, but the consequences show up in your mailboxes, chat tools, SSO flows, and admin consoles. That is where accounts are taken over, not in the vendor’s incident PDF.

This is the part we pay attention to most at Aegis: the way vendor incidents turn into fresh, highly believable stories for attackers to use in phishing and business email compromise.

One natural reaction to this AI supply-chain mess is to stop sending data to so many vendors and to run more models yourself.

That can be a good move, as long as you do not simply rebuild the same weak patterns inside your own perimeter.

A healthier posture around open-source models usually has three characteristics. First, the models run in your own environment: your VPC, your cluster, your hardware. Access goes through your identity provider rather than shared secrets in a wiki. Second, experimentation is separated from production. People can try things in a sandbox with synthetic or scrubbed data without being able to point a weekend prototype directly at the most sensitive systems. Third, you treat model inputs and outputs as sensitive. Training sets, prompts, embeddings, and logs are all subject to the same policies as databases and data lakes, rather than being treated as harmless exhaust.

On top of that, you define clear data boundaries. Which data sources can a given model query? What actions is it allowed to trigger? Who can change that configuration? These are mundane questions, but they are the difference between “we run some cool open-source models” and “we can explain exactly how our models see and use customer data.”

The goal is not to swear off third-party AI altogether. It is to reduce the number of third parties that ever see rich, unfiltered views of your business, and to have a credible answer when someone asks where your models run, what they are trained on, and who else could get to that data.

Our focus at AegisAI is the intersection of email, identity, and AI. We spend our days looking at phishing, business email compromise, and social-engineering attempts that borrow context from vendors, logs, and public data.

Incidents like the Mixpanel breach matter to us because they expand the pretext library attackers can draw from. A vendor incident is not just a line in a compliance report. It is tomorrow’s subject line and the rationale for why “security” is asking someone to click a link.

When we think about our own product, we try to apply the same lens we are advocating here. We are deliberate about where our models run and what data they see. Wherever possible, we favour architectures where customer data stays under the customer’s control. And when high-profile vendor incidents happen, we treat them as early signals for new types of phishing and BEC, not as isolated stories.

We cannot stop every vendor in your stack from quietly embedding OpenAI under the hood. We can help make sure that when those vendors have a bad day, it does not silently turn into a bad month for your SOC and your users.

The Mixpanel story is one example of a broader pattern we are watching closely: attackers using AI to make better use of vendor data, and vendors using AI in ways that quietly expand your attack surface.

We explore that pattern in more detail in our latest report:[AI-Powered Spearphishing at Scale]

In the report, we cover:

If you are rethinking your own AI supply chain after the Mixpanel incident, it is a useful companion to this post.